Popular

Latest From the Show

How to Make Homemade Sauerkraut | Fermentation King Sandor Katz

Q&A with Organizational Pro Peter Walsh + Dermatologist Shares A…

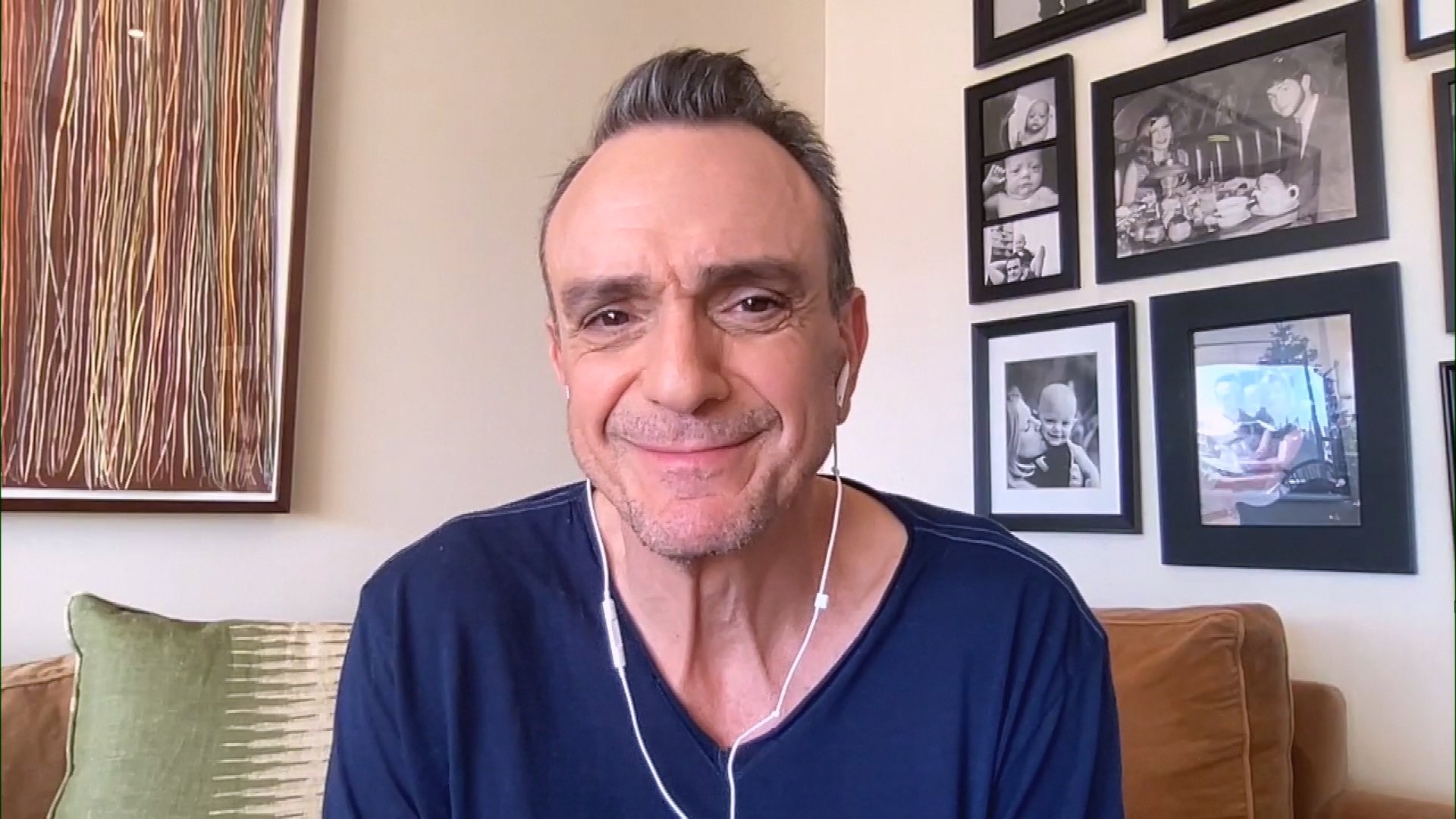

Actor Hank Azaria + Freezer Meals + Artichokes 2 Ways with Rach

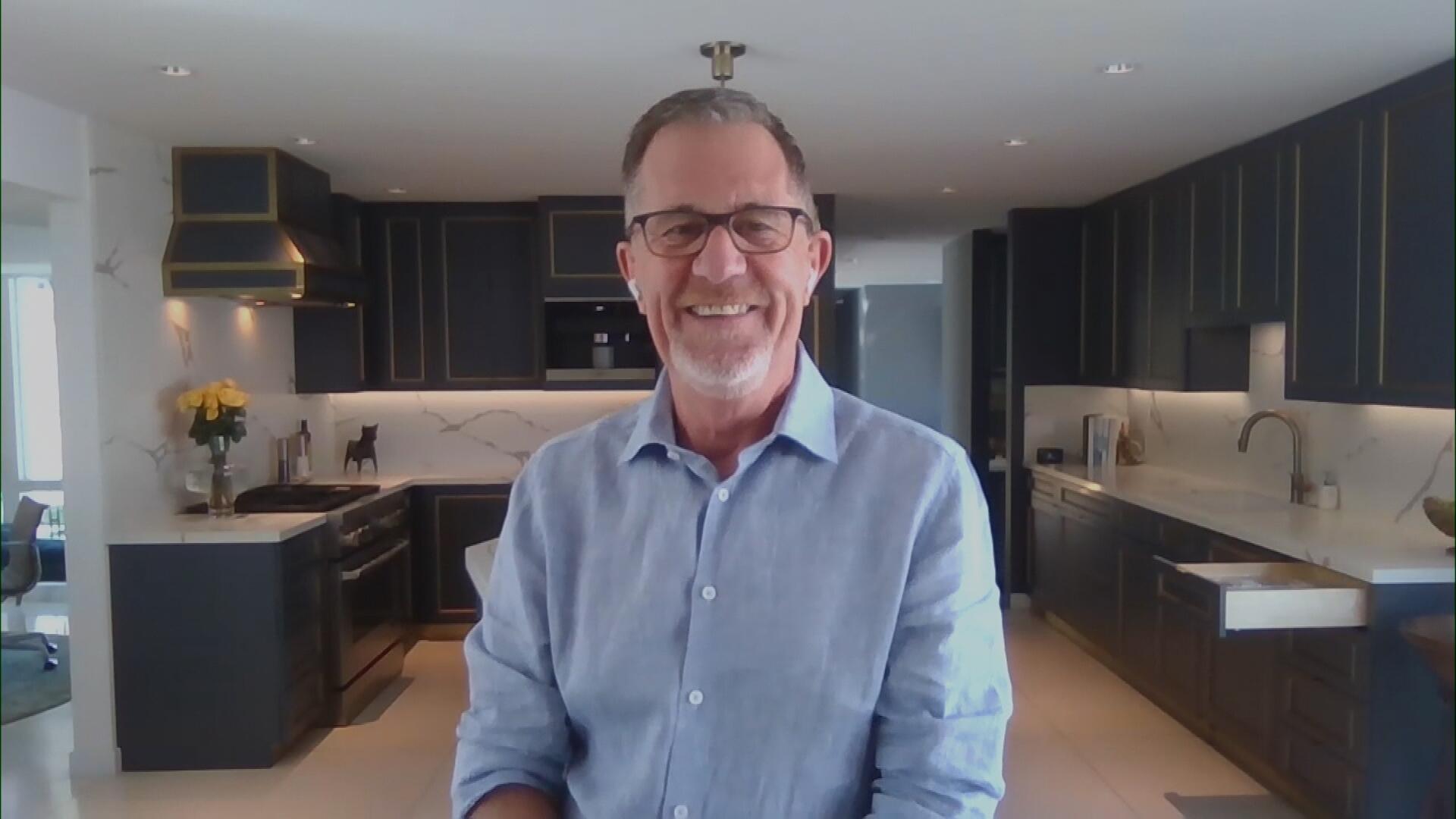

See Inside Barbara Corcoran's Stunning NY Apartment + It's Steak…

How to Make Chicken and Lobster Piccata | Richard Blais

Donnie Wahlberg Spills Details About NKOTB's First Ever Conventi…

Donnie Wahlberg + Jenny McCarthy Say Rach Is Such a "Joy" + Look…

The Best Moments From 17 Seasons of the Show Will Make You Laugh…

How to Make Crabby Carbonara | Rachael Ray

Rach Chats "Firsts" In Flashback From Our First Episode Ever In …

How to Make Apple-Cider Braised Pork Chop Sandwiches with Onion …

Rach's Chef Pals Say Goodbye to Show in Surprise Video Message

How to Make Sesame Cookies | Buddy Valastro

How to Make Tortilla with Potatoes, Piquillo Peppers and Mancheg…

How to Make Shrimp Burgers | Jacques Pepin

How to Make Spanakopipasta | Rachael Ray

Andrew McCarthy Chokes Up Discussing Emotional Trip to Spain wit…

Celebrity Guests Send Farewell Messages After 17 Seasons of the …

Celebrity Guests Send Farewell Messages After 17 Seasons of the …

Andrew McCarthy Teases Upcoming "Brat Pack" Reunion Special

Michelle Obama Toasts Rach's 17 Years on the Air With a Heartfel…

With more than 25 years of experience fermenting foods and six books on the topic, it's no wonder Sandor Katz has been dubbed the "Fermentation King." Here, he shares his sauerkraut recipe, which blows away typical store-bought sauerkraut. Note that it requires a 1-quart wide-mouth jar or a larger jar or crock, and takes a minimum of 3 days, but can go for 3 months (or beyond).

"The sauerkraut method is also referred to as dry-salting, because typically no water is added and the juice under which the vegetables are submerged comes from the vegetables themselves. This is the simplest and most straightforward method, and results in the most concentrated vegetable flavor." –Sandor

For recipes that use sauerkraut, check out Rach's Kielbasa and Pierogi Tray Bake with Sauerkraut and Rocco DiSpirito's Breakfast Reuben.

Ingredients

- 2 pounds of vegetables per quart, any varieties of cabbage alone or in combination, or at least half cabbage and the remainder any combination of radishes, turnips, carrots, beets, kohlrabi, Jerusalem artichokes, onions, shallots, leeks, garlic, greens, peppers, or other vegetables

- Approximately 1 tablespoon salt (start with a little less, add if needed after tasting)

- Other seasonings as desired, such as caraway seeds, juniper berries, dill, chili peppers, ginger, turmeric, dried cranberries, or whatever you can conjure in your imagination

Yield

Preparation

Prepare the vegetables. Remove the outer leaves of the cabbage and reserve. Scrub the root vegetables but do not peel. Chop or grate all vegetables into a bowl. The purpose of this is to expose surface area in order to pull water out of the vegetables, so that they can be submerged under their own juices. The finer the veggies are shredded, the easier it is to get juices out, but fineness or coarseness can vary with excellent results.

Salt and season. Salt the vegetables lightly and add seasonings as you chop. Sauerkraut does not require heavy salting. Taste after the next step and add more salt or seasonings, if desired. It is always easier to add salt than to remove it. (If you must, cover the veggies with dechlorinated water, let this sit for 5 minutes, then pour off the excess water.)

Squeeze the salted vegetables with your hands for a few minutes (or pound with a blunt tool). This bruises the vegetables, breaking down cell walls and enabling them to release their juices. Squeeze until you can pick up a handful and when you squeeze, juice releases (as from a wet sponge).

Pack the salted and squeezed vegetables into your jar. Press the vegetables down with force, using your fingers or a blunt tool, so that air pockets are expelled and juice rises up and over the vegetables. Fill the jar not quite all the way to the top, leaving a little space for expansion. The vegetables have a tendency to float to the top of the brine, so it's best to keep them pressed down, using one of the cabbage's outer leaves, folded to fit inside the jar, or a carved chunk of a root vegetable, or a small glass or ceramic insert. Screw the top on the jar; lactic acid bacteria are anaerobic and do not need oxygen (though they can function in the presence of oxygen). However, be aware that fermentation produces carbon dioxide, so pressure will build up in the jar and needs to be released daily, especially the first few days when fermentation will be most vigorous.

Wait. Be sure to loosen the top to relieve pressure each day for the first few days. The rate of fermentation will be faster in a warm environment, slower in a cool one. Some people prefer their krauts lightly fermented for just a few days; others prefer a stronger, more acidic flavor that develops over weeks or months. Taste after just a few days, then a few days later, and at regular intervals to discover what you prefer. Along with the flavor, the texture changes over time, beginning crunchy and gradually softening. Move to the refrigerator if you wish to stop (or rather slow) the fermentation. In a cool environment, kraut can continue fermenting slowly for months. In the summer or in a heated room, its life cycle is more rapid; eventually it can become soft and mushy.

Surface growth. The most common problem that people encounter in fermenting vegetables is surface growth of yeasts and/or molds, facilitated by oxygen. Many books refer to this as "scum," but I prefer to think of it as a bloom. It's a surface phenomenon, a result of contact with the air. If you should encounter surface growth, remove as much of it as you can, along with any discolored or soft kraut from the top layer, and discard. The fermented vegetables beneath will generally look, smell, and taste fine. The surface growth can break up as you remove it, making it impossible to remove all of it. Don't worry.

Enjoy your kraut! I start eating it when the kraut is young and enjoy its evolving flavor over the course of a few weeks (or months in a large batch). Be sure to try the sauerkraut juice that will be left after the kraut is eaten. Sauerkraut juice packs a strong flavor, and is unparalleled as a digestive tonic or hangover cure.

Develop a rhythm. Start a new batch before the previous one runs out. Get a few different flavors or styles going at once for variety. Experiment!

Variations: Add a little fresh vegetable juice or "pot likker" and dispense with the need to squeeze or pound. Incorporate mung bean sprouts . . . hydrated seaweed . . . shredded or quartered brussels sprouts . . . cooked potatoes (mashed, fried, and beyond, but always cooled!) . . . dried or fresh fruit . . . the possibilities are infinite . . .

Excerpted from Wild Fermentation by Sandor Ellix Katz. Copyright © 2016 by Sandor Ellix Katz. Used with permission by Chelsea Green Publishing. All rights reserved.